this review was unfortunately killed so i am sharing it here instead. i know like 75% of you are subscribed because you like rachel’s sections of the newsletter lol, we will write another one soon.

Cormac McCarthy is perhaps our greatest living writer. For the first half of his career, he was a proper heir to Herman Melville and William Faulkner, writing bracing and propulsive novels in extraordinarily beautiful language. In later books like No Country for Old Men and The Road, he often dropped his lyricism for clipped prose that, despite its opposite approach, rendered a vivid and punishing world all the same.

But from the first page of The Passenger, his first novel in 16 years, something is not right. The opening image is an upsetting one: a woman who has died by suicide hangs frozen from a tree. In earlier books, McCarthy would almost certainly have crafted a disturbing portrait that readers couldn’t shake. Instead, he drifts and stumbles:

“It had snowed lightly in the night and her frozen hair was gold and crystalline and her eyes were frozen cold and hard as stones. One of her yellow boots had fallen off and stood in the snow beneath her. The shape of her coat lay dusted in the snow where she’d dropped it and she wore only a white dress and she hung among the bare gray poles of the winter trees with her head bowed and her hands turned slightly outward like those of certain ecumenical statues whose attitude asks that their history be considered.”

Additional words pile-up instead of expanding. The litany of “ands” prevents a flow or rhythm from developing. The comparison to “ecumenical statues” is oddly tentative and vague. Rather than imbuing his scene with biblical feeling, he lazily references a symbol of it.

This unpolished and unbalanced mode pervades the book. The Passenger centers on a pair of siblings, the children of a man who worked on the atomic bomb. Alicia, the woman from the opening paragraph, is a math genius with schizophrenia. Bobby, her older brother, is a smart-but-not-as-smart salvage diver. They are in love with one another but this incestuous desire is an afterthought. The structure of the book gives them each substantial time but never in the same scene. Alicia’s sections, all italicized, consist almost exclusively of conversations between her and her hallucination, The Kid. Though McCarthy attempts to liven them up with zany details--The Kid has flippers for hands, often rhymes, and botches a joke about Mickey and Minnie Mouse getting divorced because she was fucking Goofy--but they rarely rise past the level of a tossed off interlude. This is perhaps an unfortunate symptom of the fact that The Passenger is one (much longer) piece of a two-part narrative. Stella Maris, the forthcoming companion novel, centers on Alicia.

Bobby’s sections take place mostly in New Orleans in 1980, after Alicia has already died. Though he spends a lot of time in bars having meandering conversations with acquaintances and coworkers, his portions are occasionally more dynamic.

In his opening scene, Bobby and a team of other divers are searching a plane that has landed in the water. There are seven dead bodies but eight names on the manifest. The informational box from the plane is missing. There is no explanation and this crash is never mentioned on the news. His plot, if one can call it that, is driven by the mysterious agency or agencies with an interest in keeping it quiet that continually send men in his pursuit. What they want and why they want it never becomes clear. Withholding can be an effective way to build tension: an unknown group with unknown desires and unknown power cannot be effectively stopped or appeased.

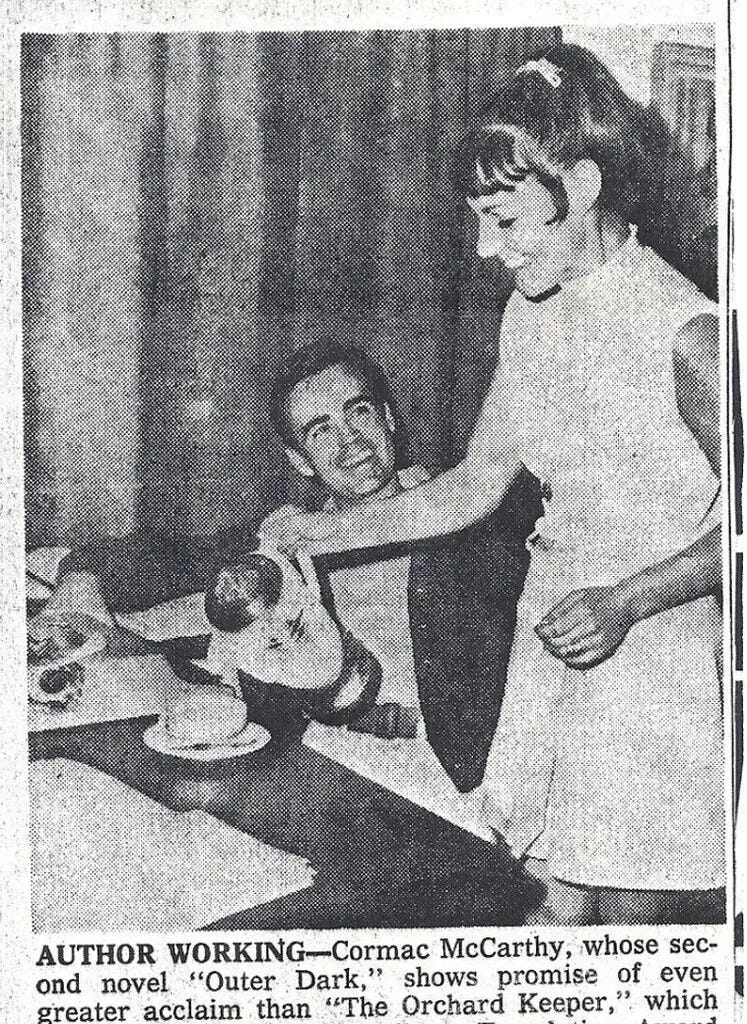

McCarthy’s books are full of forces like this: Chigurgh in No Country for Old Men is an inevitable killer; the incestuous siblings of Outer Dark are haunted forever by their sin; Lester Ballard in Child of God, increasingly isolated from society, becomes a serial killer; The Judge in Blood Meridian is one of the most terrifying, inescapable figures in literature. Even when the malevolent presence was not literally on the page, it always loomed. In The Passenger, there are ominous break-ins and there are suspicious deaths and there is a control exerted over Bobby that he cannot escape or explain. These are suitable ingredients but they are established with such little urgency or importance, they seem like inconveniences and bummers instead of dreadful omens.

The aimlessness is made worse by oddly boring and conventional dialogue. McCarthy repeatedly leans on antecedent confusion to give his otherwise stagnant conversations some movement. An example:

“I said why would I set fire to my own apartment? And anyway, we’re only renting for God’s sake. How are you going to collect on that?...Obviously the cats caught fire first is what started the whole thing. They’re just so fucking dumb.

The cats?

No, not the cats. The fucking insurance people.”

McCarthy pulls these little reversals, perfectly at home in any Marvel TV show, a handful of times to no end. Towards the beginning of the book there are multiple instances within ten pages.

These repetitions feel less like the product of intentional meaning making and more like a lack of attention to detail. Combined with other distractions, like two bizarre and inconsequential interjections from an otherwise absent omniscient narrator, the book starts to feel unedited. McCarthy’s longtime editor, Gary Fisketjon, was fired in 2019 for a “breach of company policy,” perhaps meaning The Passenger was received and edited by someone without a preexisting working relationship. An unenviable position, to be sure. But no matter how it happened, the first 200 or so pages of the novel have the feeling of a first draft.

This feeling is compounded by the shocking moments of brilliance that appear like a ghost of novelist past. There are passages, like when Bobby recalls the image he cobbled together of the bomb tests his father helped make possible, which are as arresting as any in his oeuvre:

"Lying face down in the bunker. Their voices low in the darkness. Two. One. Zero. Then the sudden whited meridian. Out there the rocks dissolving into a slag that pooled over the melting sands of the desert. Small creatures crouched aghast in the sudden and unholy day and then were no more. What appeared to be some vast violetcolored creature rising up out of the earth where it had thought to sleep its deathless sleep and wait its hour of hours."

Images like this are so rare and special. Lest it seem like an accidental muscle spasm, he conjures another mere sentences later.

“His father. Who had created out of the absolute dust of the earth an evil sun by whose light men saw like some hideous adumbration of their own ends through cloth and flesh the bones in one another's bodies.”

That these paragraphs are so remarkable, unfortunately, only makes The Passenger more disappointing. No image, no matter how well crafted, can revive the momentumless novel. By the time it feels like McCarthy wakes up, there is too little on the level of character or plot with which to work. It’d be easier to swallow if there was no vibrancy in the book. He’s had a long career and a long layoff, maybe he just doesn’t have it anymore. It’s much harder when he’s letting beautiful paragraphs go to waste.

excellently, written!

I'm sorry this got killed, it's a good review!